Publics Are Plural

A Conversation Between Jonathan Jae-an Crisman and Marisa Turesky

Post date: October 21, 2021

Marisa Turesky is a PhD candidate at USC. Jonathan Jae-an Crisman is Assistant Professor of Public & Applied Humanities at the University of Arizona. After viewing Pride Publics: Words and Actions with curator and artist Rubén Esparza, they met up to have a conversation about the exhibition and its themes.

Jonathan Jae-an Crisman: I thought maybe we could start by reflecting for a moment just on the title. I know that it is a title that was conceptualized by Umi Hsu from One Institute, and then re-interpreted and utilized by Rubén Esparza. I love it because it is such a provocative title, and one so relevant to thinking about cities and public space. It’s a very different take than older sensibilities of queer space which were very centered around ideas of obfuscation—fortress-like spaces with windowless bars, secret places where one could act out queer desire.

In a way, it connects to the heart of Pride, which has its roots in the celebration of queer bodies in public space as a protest against police violence. But then I’m using “public” as an adjective here, as in “public pride.” If we really take the title at its face value, we’re talking about not just one “Pride public” but multiple “Pride publics.” In other words, the title suggests moving beyond some sense of a singular homonormative Pride public, and celebrating the multiple and diverse bodies and communities that make up this queer family of ours.

Marisa Turesky: I think the title is pretty damn great for many reasons, one of which is how well it conveys the multiplicity—the diversity, the ever-changing nature—of spaces that queers have been creating for a very long time to transform public spaces into spaces of queer desire (think: cruising!). Pride certainly represents a pivotal manifestation in queer place-claiming tactics. It felt so special that the “publics” aspect of the installation was not just in semantics. We actually could just walk down a West Hollywood sidewalk and engage with an intergenerational queer dialogue. We got to walk alongside these gorgeous, gender-fucking changemakers and they weren’t there alone.

“The Heterosexist Nature of Forgetting”

Marisa Turesky: One of the most fundamental lessons I’ve learned from my work with folx at ONE is that we have a wonderfully rich LGBTQ+ history, both here in LA and globally. Rubén asked each artist to choose a quote from a historical LGBTQ+ changemaker who has been important to them and, in doing so, he demonstrates a resistance to what I might call “the heterosexist nature of forgetting.” This multigenerational public is not so easy to find at Pride…or many other queer spaces. I think this multigenerational piece also speaks to what you said about the roots of Pride being an abolitionist movement. Knowing our own history and ancestors seems critical to understanding how we got to where we are, and to being able to plan for the revolutions ahead. How did you see this in the exhibit?

JJC: Wow, “the heterosexist nature of forgetting”! That really hits hard. This idea is new to me, but I think I see what you’re getting at. There is traditionally a heterosexist privileging of the new, the singular, the heroic, which pushes the past and the collective out of sight and out of mind. And so it is a queer and feminist practice to remember. It takes a lot of unvalued labor to remember—and to remind others!

I’m also thinking of work around maintenance here, which artists like Mierle Laderman Ukeles have championed, or ideas of community and care emphasized by the curator and artist Gwyneth Shanks during her time at the Walker. And, intergenerational work really gets at the heart of this, too—there is a need for older LGBTQ+ adults to lift up younger people in the community, and support their work, and for younger generations to build on the foundations of older generations rather than imagining their work coming out of some kind of tabula rasa. Of course, all of this is set against the backdrop of the HIV/AIDS epidemic which killed a generation of queer and trans people who would now be elders, imparting wisdom and remembering for all of us. A huge piece of our collective memory was essentially cut out from our social brain, which can lead to real difficulties in achieving a kind of intergenerational practice.

All of this to say that this is precisely why Pride Publics is powerful: it sets up a dialogue between queer artists and changemakers on multiple dimensions. Between us, the public, and them, amongst the artists, the curator, and those involved in the production of the exhibition, but also—and I think most intriguingly—between the contemporary and the “historical” changemaker.

Getting back to your comment about Pride as an abolitionist movement, one of the moments that I really loved in the exhibition was how Patrisse Cullors was featured in the line-up as an artist (and she quoted the great Angela Davis), but then she was also quoted by C. Jerome Woods, as *his* changemaker. He chose this quote from Patrisse: “In high school, I came out to my friends as queer. My entire world opened up; this was a monumental step toward unveiling my truest self.”

This is such a reminder that from the first Pride in 1970, which paid homage to the one-year anniversary of the Stonewall uprising, to now, where one of the leaders of the contemporary abolition movement is a queer Black artist, that the idea of “Pride publics” is fundamentally abolitionist in nature. How do you think about Pride as connected to abolition?

MT: You really queered the phrase, “the heterosexist nature of forgetting”—incredible! I was thinking about it much more literally as: whose voices and lives get to be remembered? I was riffing on Karen Burns’ (2019) phrase in which she uplifts the importance of feminist scholarship to resist the gendered nature of forgetting (130). She pulls from collective memory studies to critique the way in which political and institutional memories favor remembrance of dominant voices and histories (i.e., white, straight people). In other words, LGBTQ+ people’s memories’ and histories’ are often not recorded—therefore they are forgotten—and remembering them is critical in our struggle to “queer” the narrative when it comes to culture, policies, and places.

As you’ve noted with Ukeles and Shanks as critical examples, care and community are so integral to queer collective memory, as well as to broader notions of queer politics. In the exhibit, we see how this care percolates in so many different ways. For instance, Angela Divina lives this care through her ancestral traditions of nourishing her people with cooking. I am so taken with the visceral imagery of this queer collective memory being “cut out from our social brain,” as you describe it. As Rubén illustrated, this is even more true for QTBIPOC folx whose lives, faces, memories, and visions often go unwritten and forgotten even within queer spaces and institutions.

This is especially true if we look to the planning of LA Pride 2020. Initially, Pride organizers seem to abandon an abolitionist vision as they cozied up to the LAPD, erasing many LGBTQ+ people, particularly QTBIPOC, who continue to be brutalized and regulated by cops everyday. I love how you’ve lifted up Patrisse’s presence in different parts of Pride Publics to reflect the deep connection between current abolition movements and Pride’s genealogy, which you and I are writing about as being rooted in remembrance for rebellions against police brutality with our upcoming article in Urban Planning. As Jac sm Kee wrote: “memory is resistance.” Pride Publics seems to enact that notion by locating contemporary QTBIPOC artists and changemakers in queer and trans lineages, by seeing these revolutionaries as living history, in and of themselves.

The Queer Ethic of Collective Production

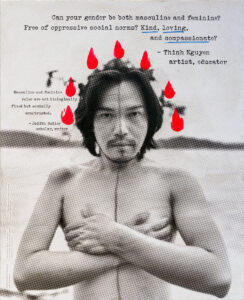

MT: You mention the many, simultaneous conversations happening within this one piece. In the same way that the artists are in a dialogue with the queer and trans community and ancestors through their chosen quotes, I want to lift up how the layering of colors and paints allows for a kind of conversation between the public and the installation itself. This openness to fluid changes seems to embody a queer politic. First, Rubén highlighted, drew, and wrote on the canvas as a way of interacting with the artists’ portraits. He then invited the artists to annotate themselves. Finally, the artists offered their communities the opportunity to do so. For instance, someone drew hot pink flames (or water drops?) outlining Thinh Nguyen’s head and another person penned “leather gave me a family” next to Rogelio Ramires. The layers of responses and reactions seemed to add such flashy glimpses of impermanence and collectivity.

JJC: Ah, yes, very important point about who gets to be remembered. And, in fact, it goes beyond a notion of privilege: it’s not simply that heteronormative lives “get to be remembered” but also, and perhaps worse, queer lives are often actively and intentionally erased. Society finds it easier and thus would prefer to forget these bodies that don’t fit into the predefined shapes it provides. There is so much wonderful recent work about queering archives and archival justice that gets at these ideas, from people like Cait McKinney and Charles Morris. Then there is the strange process of queer lives having all of their wonderful diversity normalized and straightened into a socially digestible category so that the ones that we actually do see and remember begin to fit within a “homonormative” mold. And, indeed, this has often been the critique of recent Pride events: they are more corporate, whiter, more male. Instead of an abolitionist protest, it has often become a marketing opportunity. As devastating as it has been to see Pride interrupted upon its 50th anniversary, perhaps it was an important moment for pause and reflection. Against the backdrop of the murder of George Floyd, we were able to remember that one of the original demands of LA Pride was to end police brutality.

Against all this talk about queering archives, we can’t not mention the fact that Pride Publics was organized by the community partner to the world’s largest LGBTQ+ archive, ONE Archives at the USC Libraries! The recent exhibitions from One Institute have really grappled with this issue of homonormativity with shows like Metanoia which, per its introduction, “centers primarily on the contributions and experiences of Black cis and trans women, and cis and trans women of color who have always been at the forefront of movement work, but who are often found at the margins of AIDS archives, art shows, and histories.”

And for Pride Publics, Rubén Esparza noted his intentionality behind highlighting queer POC, his drawing from the activism of Robert Vazquez-Pacheco as one of the few non-white people that we know about in the legendary ACT UP movement. The street portraits show the faces of these diverse queer artists, and their “quick and dirty” quality, to quote Esparza, gets at the vitality of street art and street protest that was so central to ACT UP’s activism.

I think you’re absolutely right that their openness and fluidity shows a kind of queer ethic of collective production. I think the most powerful and meaningful art gets at the most basic ideas of the human condition but are often unable to be monetized within the commercial art market, and are very difficult to claim single authorship over. Who owns the hot pink flames on Nguyen’s portrait? Who is the author of the splattered red paint of an ACT UP protest? As we wrap up, I’m wondering if any of the quotes in the portraits especially speak to you, or resonate with anything you’re thinking and writing about these days?

Genealogies and Geographies

MT: Jonathan, you so beautifully summed up all the key themes and theories that had my head spinning from Pride Publics: homonormativity, archival justice, multiplicity, collectivity, the violence of erasure. I’m with you. PP demonstrates the kinds of queer world-making that can come from grounding ourselves in multigenerational LGBTQ+ thoughts and spaces, which is actually fundamental to my dissertation. I am seeking to preserve some of our living history by recording spatial oral histories with lesbians aged 60-85 in LA. Many spaces—LGBTQ+ or not—are very youth-oriented and can be downright ageist. Little is known about how urban places, services, and policies can better serve our LGBTQ+ community as folx age so I explore how aging changes (or doesn’t) the kinds of places lesbians need and desire.

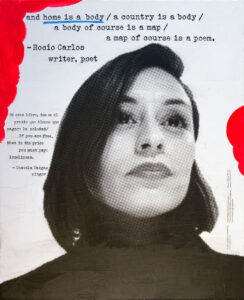

Great question about the quotes. So many of them struck chords and manifested different emotions from me. At this moment, Rocío Carlos’ own words, as well as their chosen quote by Charval Vargas, are really sticking with me. From their book of poetry with Rachel MacLeod Kaminer, Attendance, Carlos writes:

and home is a body / a country is a body / a body of course is a map / a map of course is a poem.

It reminds me of Gloria Anzaldúa and Hélene Cixous as they break down these borders between the corporeal and the spatial, the corporeal and the political, the geographic and the semantic. This breaks down the rigid walls of categorization; categorizations that can entrench habits to “become the enemy within” (1987: 371). To echo Cixous’ poetic manifestos, we write ourselves into the world. So that we may be heard or seen, even touched or tasted. What quote(s) strikes you, Jonathan?

JJC: Such a great selection. And Gloria Anzaldúa, a total icon, was also quoted by Jaklin Romine! “I will no longer be made to feel ashamed of existing. I will have my voice, Indian, Spanish, white. I will have my serpent tongue end my woman’s voice, my sexual voice, my poet’s voice. I will overcome the traditions of silence.”

Something that I have been working on for a while is an exploration of queer diasporic Asian creative practices and their intersections with urban and collective life. It’s an academic project, but also a community one—in the form of a party that I throw with a bunch of other delightful people called QNA. So as for quotes that strike me, I couldn’t help but ruminate on the incisive words posed by some of the queer Asian folks featured in Pride Publics.

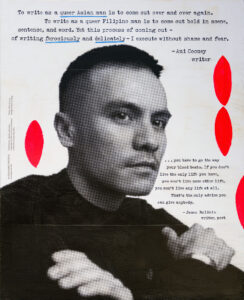

Ani Cooney writes “To write as a queer Asian man is to come out over and over again” and he quotes the great James Baldwin: “If you don’t live the only life you have, you won’t live some other life, you won’t live any life at all.” I see this as such a beautiful encapsulation of the personal and internal process of becoming for queer folks.

There are also words that capture the equally important external and collective process of shared creation for queer folks: Jennifer Moon writes “Continuous expansion beyond binaries, hierarchies, and capital that keep us locked in a 5% universe ☄️🌈 #revolutionordeath.” (I love an emoji moment.) And they quote the late José Esteban Muñoz: “Queerness is a structuring and educated mode of desiring that allows us to see and feel beyond the quagmire of the present. The here and now is a prison house. We must strive, in the face of the here and now’s totalizing rendering of reality, to think and feel a then and there.” I always return to this idea of queerness being, more than anything else, a political position that helps us break free from “the quagmire of the present.”

By publicly honoring the QTBIPOC artist-leaders of our community, Pride Publics becomes a collective memory project that’s an act of resistance. Its occupation of public space begins to heal the violence of historic LGBTQ+ erasure, while it also celebrates people’s beautiful differences and reminds us to imagine radical futures.

All exhibition photos by Jon Viscott

Authors

Marisa Turesky spends most of her days reading, writing, and thinking about queer spaces, urban history, and community planning. As a PhD candidate at USC, she examines how identities and cultures shape peoples’ access to urban places, services, and housing.

Jonathan Jae-an Crisman is Assistant Professor of Public & Applied Humanities at the University of Arizona. Most recently, he has been working with the community in Little Tokyo around art and gentrification, and he also co-organizes a queer Asian party in LA called QNA.